Frozen Shoulder: Does It Resolve By Itself?

What is Frozen Shoulder?

Frozen shoulder also known as adhesive capsulitis, is an insidious painful condition of the shoulder persisting more than 3 months. This inflammatory condition that causes fibrosis(thickening) of the glenohumeral joint capsule is accompanied by gradually progressive stiffness and significant restriction of shoulder range of motion. However, you may develop symptoms suddenly and have a slow recovery phase. The recovery is satisfying in most of the cases, even though this may take up from 12-48 months.

A thickened coracohumeral ligament at the rotator interval has been reported as one of the most specific manifestations of frozen shoulder as it becomes taut during ER.

Signs and Symptoms of a Frozen Shoulder

Signs and Symptoms of a Frozen Shoulder

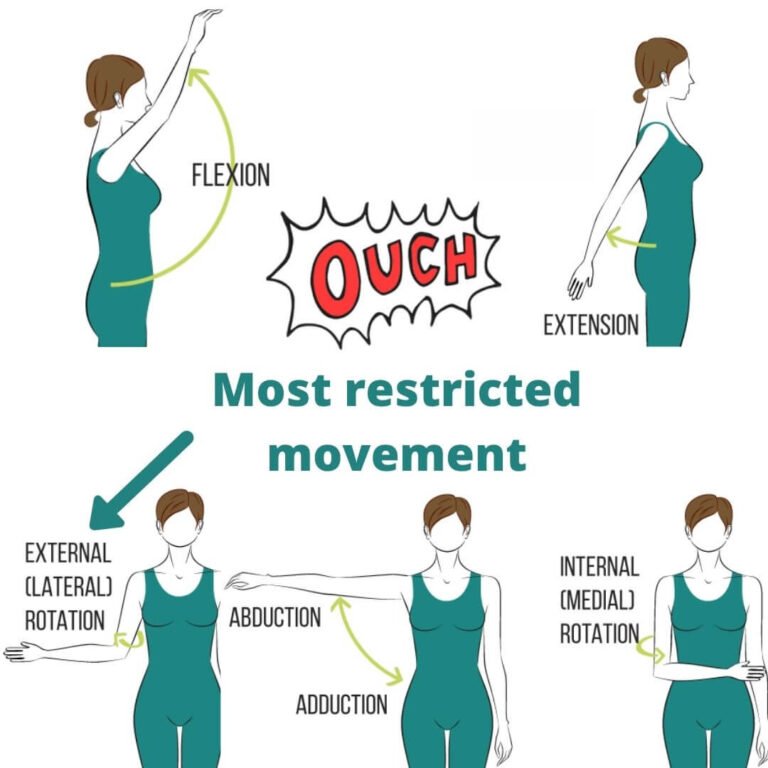

Patients suffering from early frozen shoulder usually present with a sudden onset of one sided front shoulder pain. The typical symptoms comprises of passive and active range of motion restriction, first affecting external rotation and later abduction of the shoulder.

In general, depending on the stage and severity, the condition is self-limiting, interfering with activities of daily living, work, and leisure activities.

Functional impairments caused by frozen shoulder consist of limited reaching, particularly during overhead (e.g., hanging clothes) or to-the-side (e.g., fasten one's seat belt) activities.

Patients also suffer from restricted shoulder rotations, resulting in difficulties in personal hygiene, changing of clothing and brushing their hair.

During the painful phase, night pain may be present as the body increases blood flow to your shoulder to try and lay down new tissue.

Another common related condition with frozen shoulder is neck pain, mostly derived from overuse of cervical muscles to compensate the loss of shoulder motion.

(Mezian et al, 2022).

How do Physios diagnose Frozen shoulder?

A physiotherapy assessment of the joint, musculature, signs and symptoms will be the best and most accurate way to diagnose a frozen shoulder.

Imaging tests — such as X-rays, ultrasound or MRI — can rule out other problems of the shoulder.

How does one get frozen shoulder?

The cause of frozen shoulder is still unknown, however some risk factors are:

Most often in people with chronic diseases, especially diabetes(with prevalence up to 20%), thyroid issues and stroke

Most often in people age 50-60 years old

After Shoulder Injury/Surgery

Slightly more often in women, especially post-menopause.

Statistically, frozen shoulder affects around 2-5% of the population. It should also be noted that 20% of patients develop similar symptoms in the opposite shoulder. Bilateral simultaneous involvement could be observed in 14% of the patients.

(Pandey & Madi, 2021).

What does the evidence say about frozen shoulder recovery patterns?

In 1940s, it was proposed that frozen shoulder progresses through a self-limiting natural history of painful, stiff and recovery phases, leading to full recovery without treatment.

In historical literature, frozen shoulder is broken down into 3 stages, which are:

Freezing: In 2-9 months, there is a gradual onset of diffuse, severe shoulder pain that typically worsens at night.

Frozen: The pain will begin to subside during the frozen stage with a characteristic progressive loss of glenohumeral flexion, abduction, internal rotation and external rotation

Thawing: During the thawing stage, the patient experiences a gradual return of range of motion that takes about 5–26 months to complete.

Recent literature suggests that these stages are probably not something to rely on, to think how you sort of just go through this process and recover as time passes. And although people tend to get stiff somewhere along the line, it's not always a black and white transaction.

In 2017, a systematic review conducted by Wong et al suggested that there is no good/validated evidence to say people would systematically recover over time without treatment. People without treatment interventions would have a shorter window to get better, and have larger impairments at the end of treatment time; 12-48 months was the overall time frame to get better with the first 12 months being the most important.

Key takeaway from this segment:

The duration of ‘traditional clinicopathological staging’ of frozen shoulder is not constant and varies with the intervention(s).

Manual Therapy for Frozen Shoulder

Treatment of Frozen Shoulder

By and large, conservative treatment of frozen shoulder is successful in up to 90% patients. Only a few require operative intervention in the form of manipulation under anaesthesia (MUA) or arthroscopic capsular release (ACR).

Treatment of frozen shoulder often depends upon its stage:

Painful - Freezing stage:

Pain-relieving physiotherapy such as manual therapy, gentle range of motion (ROM), dry needling and cupping therapy can help reduce pain levels.

Physiotherapy, along with NSAIDs or steroid injection, is better in providing symptomatic relief than physiotherapy alone. However there is ongoing evidence to suggest that cortizone injection is only beneficial to the early freezing stages (0-8 weeks) and that a delayed injection would yield no difference in terms of pain relief compared to patients that did not receive any injection (Wang et al, 2017). Furthermore, to understand the long term risks involved with cortizone injections, please refer to my blog for cortizone injections.

Bit of both - Frozen stage: In this stage; pain is less, but the loss of range of motion is profound due to fibrosis of capsulo-ligament complex.

Treatment strategy should be principally aimed to gradually ‘increase and regain’ the ROM by deploying a structured and well-sustained mobilisation physiotherapy program.

In the late frozen stage, low-and high-grade mobilization techniques could be implemented to regain the ROM along with ‘muscle strengthening physiotherapy.

Gentle pendulum exercise for painful stage shoulder mobility

3. Stiffness - Thawing stage: This stage is characterised by minimal or no pain and gradually improving ROM for past several weeks.

Physiotherapy remains the MOST EFFECTIVE treatment in this stage, which aims to gradually regain the ‘functional’ followed by total recovery of shoulder ROM. Any surgical interventions are hardly required in this stage.

Summary

The cause of frozen shoulder is unclear till this day. However, current research shows patients that have received physiotherapy treatment and management plans have less risk of sustaining long term lingering effects from frozen shoulder compared to people without treatment. 12-48 months was the overall time frame to get better with the first 12 months being the most important.

Hope this helps.

Your friendly neighbourhood physio,

Tony

Have a stiff and painful shoulder for a while that hasn’t been getting better? To find out whether or not it is a frozen shoulder, click BOOK NOW for a consultation with our practitioner Tony.

Resources:

Chan, H.B., Pua, P.Y., How, C.H. 2017. Physical therapy in the management of frozen shoulder

2. Wong, C.K., Levine, W.N., Deo, K., Kesting, R.S., Mercer, E.A., Schram, G.A., Strang, B.L. 2017. Natural history of frozen shoulder: fact or fiction? A systematic review https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27641499/

3. Mezian, K., Coffey, R., Chang, K. 2022. National Library of medicine “Frozen Shoulder” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482162/

4. Pandey, V., Madi, S. 2021, Clinical Guidelines in the Management of Frozen Shoulder: An Update! https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8046676/

5. Wang, W., Shi, M., Zhou, C., Shi, Z., Cai, X., Lin, T., Yan, S. 2017. Effectiveness of corticosteroid injections in adhesive capsulitis of shoulder https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28700506/